unix philosophy

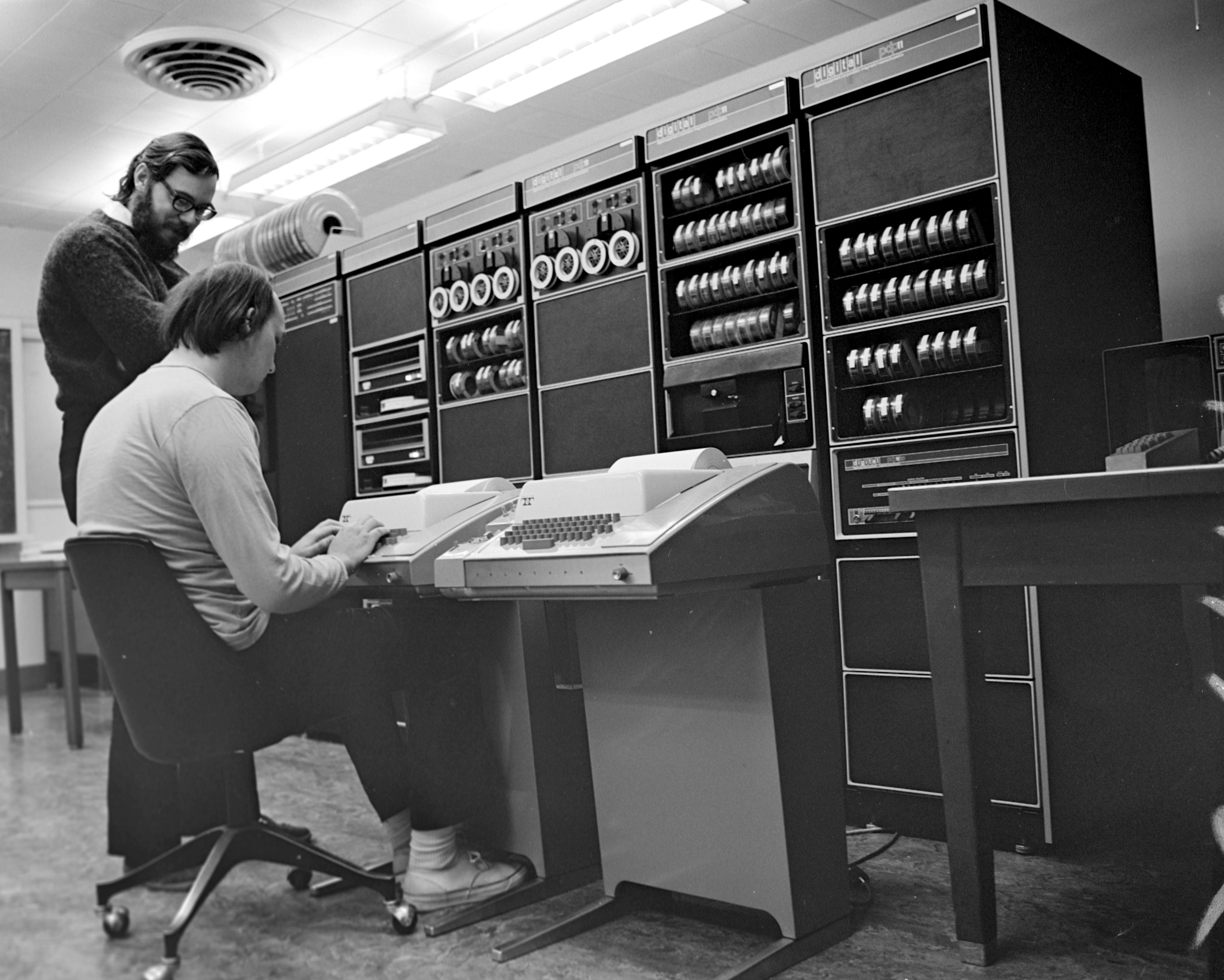

Prologue

Make each program do one thing well.

— Doug McIlroy, Bell Labs (1978)

In 1978, Doug McIlroy at Bell Labs wrote down the Unix philosophy in a few short lines. The first rule was simple: do one thing well. Nearly half a century later, this remains the most powerful and most ignored lesson in software.

The power of small things

cat reads a file. grep finds a pattern. sort puts things in order. wc counts.

These tools look plain. No flashy interface. Almost no config files. Even the help text is short. But when you connect them with a single pipe, something new is born.

cat access.log | grep "POST" | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | head -20One line. Eight words. It answers the question: "Show me the top 20 POST requests by count." No new program needed. Each tool already exists and does its own job well.

Building tools that know their place

I run multiple EKS clusters for a payments platform. Every quarter, Kubernetes versions reach end-of-life and every cluster needs an upgrade. Control plane, addons, node groups, one by one, across every environment. It is the kind of repetitive, high-stakes work where a single mistake can take down a production payment service.

When gossm, the SSM session tool our team relied on, stopped being maintained, we had two choices. Build a big AWS management tool that does everything, or build a small tool that does one thing: connect to EC2 instances through SSM.

We chose the latter. We built ij (Instance Jump) in Rust. It lists EC2 instances and starts SSM sessions. That is all. It does not manage IAM. It does not create instances. It does not collect logs. It just jumps to an instance. The name says it all.

Same story with kup, our EKS upgrade CLI. Its only job is to upgrade EKS cluster versions. Control plane, addons, managed node groups. It does not monitor. It does not deploy. It does not create clusters. Yes, it checks for PodDisruptionBudget deadlocks before draining nodes. Yes, it scans Karpenter EC2NodeClass resources for pinned AMI IDs. But these are all in service of one goal: making the upgrade go well. They do not cross the line.

If kup had tried to also create clusters, manage costs, and run deployments, it would have done none of those things well. Scope is a gift, not a cage.

The beauty of pipelines

In Unix, the pipe connects programs. In cloud infrastructure, the same pattern repeats.

CloudWatch collects metrics. YACE (Yet Another CloudWatch Exporter) converts them to Prometheus format. Prometheus stores and queries time-series data. Grafana draws dashboards. AlertManager sends alerts.

CloudWatch → YACE → Prometheus → Grafana

↓

AlertManager → SlackEach part does its own work. YACE does not try to draw dashboards. Grafana does not try to scrape metrics. Because each piece is focused, you can swap any one of them without breaking the rest. Replace Prometheus with Thanos. Use a different visualization tool instead of Grafana. The pipeline still holds.

This is the spirit of the Unix pipe. Instead of text streams, metrics flow. Instead of a shell, Kubernetes orchestrates. But the core idea is the same: small, focused parts working together.

The temptation

When you build software, temptation never stops knocking.

"Wouldn't it be nice to add this one more feature?"

You put an email client inside a text editor. You merge a package manager into a build tool. You bolt a deployment pipeline onto a monitoring system. The moment a single tool tries to do everything, it stops doing anything well.

Every time I add a new preflight check to kup, I ask myself one question: "Is this about upgrading, or is this something else?" If it is about upgrading, it belongs. If not, it becomes a separate tool.

Keeping that boundary. That is the hard part.

A letter to ls

Think about ls. It has existed since 1971, the very first version of Unix. Fifty-five years later, it still runs hundreds of millions of times every day. It lists the contents of a directory. That is all it does. And that is why it is still alive.

For a tool to survive half a century, it must not chase trends. It must stay true to one purpose. ls will not die as long as file systems exist, because it never tried to do anything beyond listing a directory.

On the other hand, gossm stopped being maintained. We had to build a replacement. But if ij does only one thing well, replacing it someday will be easy. Its interface is simple. A tool that does one thing is easy to create and easy to replace. And that is what makes a healthy ecosystem.

Is it not beautiful?

Sometimes I look at a well-made tool and feel something close to reverence.

A program that takes input, does exactly what it promises, and gives output. No waste. No decoration. No apology. There is an honesty in that kind of software. The same honesty you find in a well-made chair, a single brush stroke, or a poem with no extra words.

We call code "elegant" when it is short and clear. But I think the word we really mean is "beautiful." A tool that does one thing well has the beauty of restraint. It chose what to leave out. And that choice — the courage to be small — is what makes it art.

Closing

Write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

— Doug McIlroy

Next time you feel the urge to add one more feature, stop and ask: What is the one thing this tool does? Is it doing that well?

Doing one thing well is not a limit. It is freedom. The pipe will take care of the rest.